Yield, Harvest, Handling and Storage of Cacao

This post is also available in:

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish) ![]() Français (French)

Français (French) ![]() Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German) ![]() العربية (Arabic)

العربية (Arabic) ![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified)) ![]() Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Around 95% of the total cacao globally is produced by 5-6 million smallholder farmers from Asia, Africa, Australia, and Latin America, owning farms of 2-5 hectares (M.Kozicka et al.,2018). West Africa produces 65-73% of the total cocoa production. Most cocoa trees begin producing pods by their 4th or 5th year and can continue for another 30 years with proper care. Generally, the average cacao yield can vary from 300 to 2,000 kg per hectare (268-17844 lb/acre), depending on the region, variety, agricultural practices applied, crop density, and the age of the trees. The average yield in Ghana is around 400 kg per hectare (357 lb/acre) (C. Streck et al., 2017). Depending on the cultivar, each cacao tree can produce around 30 pods. A typical pod has 20 to 50 beans. To produce one pound of cocoa requires 400 dried beans (for 1 kg of cacao, approximately 880 dried beans are required).

For most kinds, cocoa pods are ready for harvesting when they turn a deep yellow color. Farmers use machetes and long steel instruments, such as the “go-to-hell” knife with a long handle, to cut pods from trees. The pods are split apart with solid sticks and a machete to release the seeds. Most small-scale farmers plant cocoa, harvested twice a year throughout different seasons (Main crop: September to March and Mid-Crop: May to August).

The beans are heaped and covered with banana leaves or mats. The layer of pulp that naturally surrounds the beans heats up and ferments the beans. Fermenting takes 5 to 7 days and then drying for several days under the sun. Unlike other origin countries where the mechanical heating process dries cocoa. The average Ghanaian farmer dries the cacao using the sun’s natural rays, as beans are evenly spread on raised bamboo mats. The product turns frequently, and every part of the beans is exposed to sun rays. Coupled with complete fermentation, Ghana’s cocoa beans diffuse the best natural chocolate aroma and a perfect brown color appearance.

The cocoa buying centers sell the dried, packaged, and transported fermented beans to the Licensed Buying Companies (LBCs). Before being sent, Ghanaian cocoa goes through a minimum of three quality inspection steps. This provides our consumers more comfort and trust to always purchase Ghana cocoa.

However, this traditional fermentation approach is susceptible to environmental risk factors. Periods of intense rainfall increase the time required for fermentation. Temperature changes, drought, and prolonged dry seasons affect the flavor and overall quality of the product ( Dohmen et al., 2018). Unlike Farmers in West Africa, Cocoa farmers in Latin America tend to ferment the cocoa pulp surrounding the beans using wooden boxes. In Indonesia, farmers rarely participate in the fermentation process because their production is mostly valued for cocoa butter, which is unaffected by fermentation (Neilson, 2007).

The cocoa beans are then dried after the fermenting process. Drying can lead to quality loss and productivity losses when done incorrectly and under unfavorable conditions, in line with ICCO (2000). Ghanaian farmers use mats or trays to spread out the cocoa seeds on surfaces exposed to the sun to dry the cocoa beans. Rainfall that is heavy enough to deform cocoa beans can lower quality. Droughts and dry spells will hasten the rate at which cocoa dries even though temperature variations affect the drying time. The CSC advises utilizing solar dryers, which are simple to construct using wood and transparent plastic. Solar dryers shield cocoa from excessive humidity while avoiding the GHG emissions associated with artificial drying.

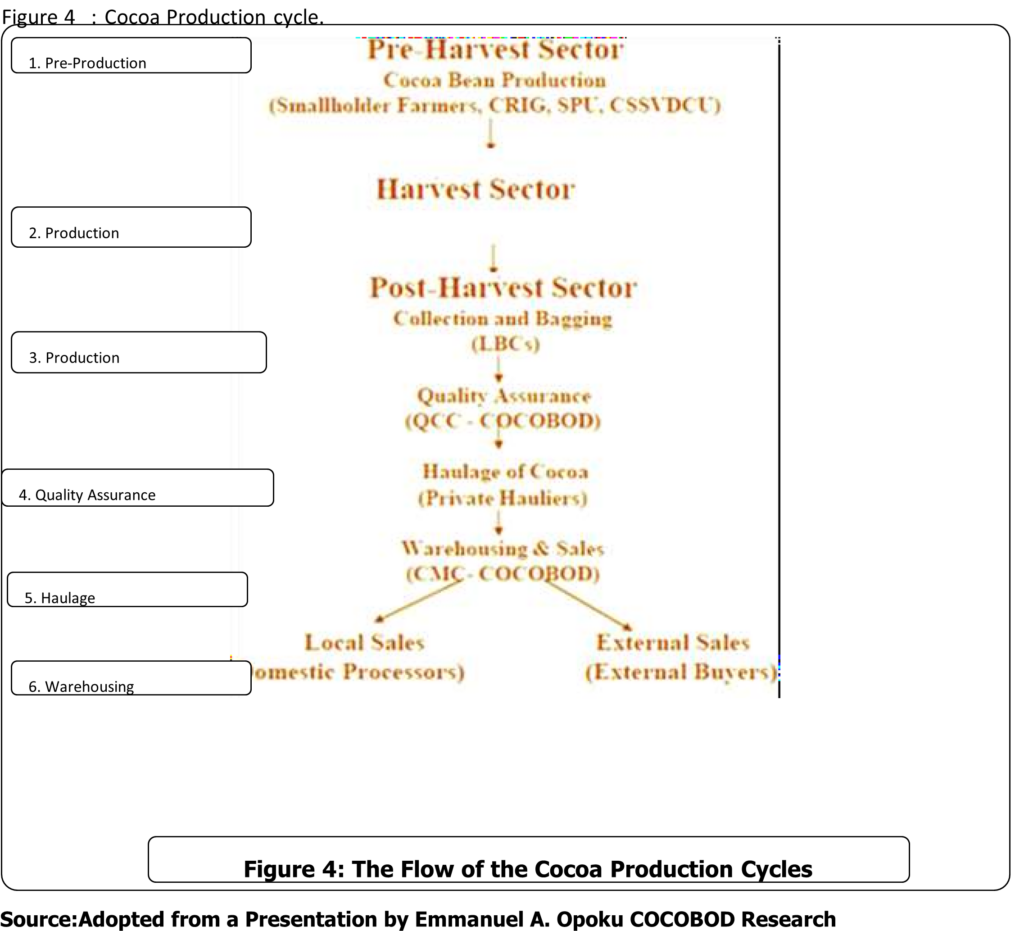

The post-harvest period is the period from the purchase of cocoa beans, quality assurance transportation, and sale.

Purchase of Cocoa Beans

LBC’s purchase cocoa from the farmers at a minimum producer price set by a Producer Price Review Committee (PPRC). After drying, the beans are bagged and sold at a buying station or a local agent of the buying company. At the cocoa buying centers, the beans undergo Quality Control Test by the LBC buying agents, following which the agents purchase acceptable cocoa. The LBC’s then move the cocoa to the main COCOBOD sheds/ warehouses in the districts, where the cocoa is further weighed and tested for humidity levels by Quality Control Unit (QCU). After testing, acceptable cocoa is taken into the warehouse, where the LBC’s will be issued with cocoa takeover receipts (CTOR’s) by the Cocoa Marketing Company.

The COCOBOD closely monitors the operations of all LBC’s. The LBC’s are required to abide by the regulations and guidelines set by COCOBOD. Prospective buyers of cocoa have to apply to the COCOBOD for consideration to be licensed as buyers. Upon vetting by an independent committee set up for that purpose, successful applicants are granted provisional licenses, which may be converted into full licenses if the COCOBOD is satisfied that the LBC has adequate operational logistics for effective operation.

Warehousing

The LBCs sell their purchased cocoa to the Cocoa Marketing Company (CMC), which issues a cocoa takeover receipt to them for payment by COCOBOD according to margins set by the PPRC. The cocoa is again checked for quality before being transferred to a pier warehouse of CMC at the port.

The various sheds and warehouses at the district and main collection sites are inspected on a regular basis by the staff of QCD to carry out disinfestations to remove damage to the bags of coco insects and rodents.

Outside of the CMC’s warehouses, the main warehouse provider in Ghana is Tarzan Enterprises and Global Haulage. The warehousing section of the value chain has an estimated value of between GHS 30 – 40 million a year.

Selling and transporting

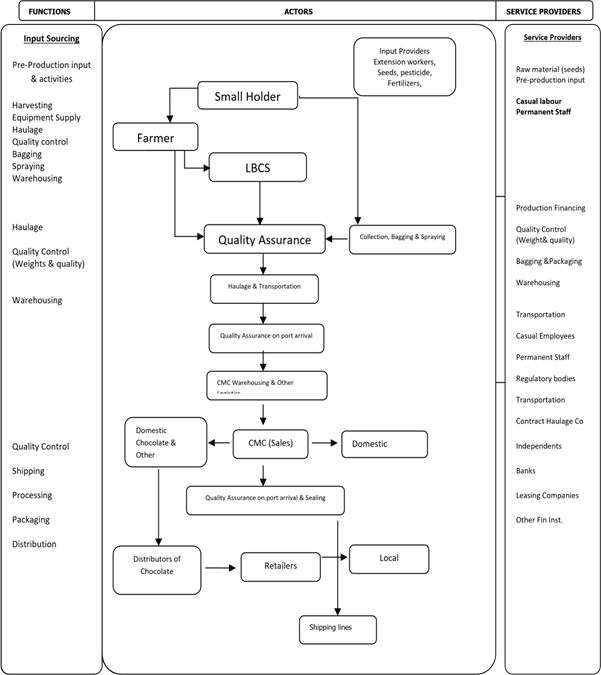

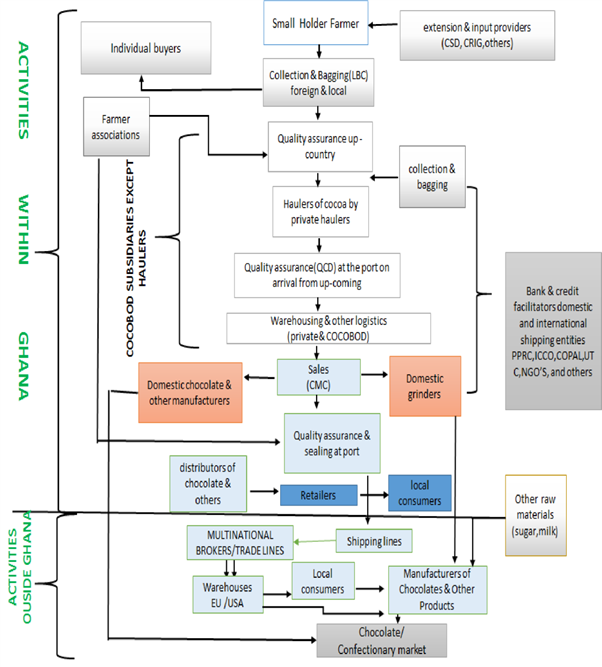

The manufacture of cocoa involves a lengthy supply chain that includes growers, buyers, transporters, traders, collectors, certifiers, storage processors, chocolatiers, and distributors. The flow chart below shows how the supply chain structure for the cocoa business is divided between activities that take place in Ghana and outside of Ghana. The essential players are named, profiled, and their specific roles in the supply chain are described. It investigates the interactions between actors and the key variables that affect behavior and guide judgment. Based on the level of processing, the cocoa supply chain can be split into four main product groups. The following are the categories:ü Cocoa beans (raw or minimally processed); ü Semi-finished cocoa products (cocoa paste/liquor, cocoa butter, cocoa powder); ü Couverture, or industrial chocolate; ü Finished chocolate confectionary products. The structure below focuses on Ghana’s domestic supply chain, which includes producing and marketing cocoa beans and semi-finished cocoa products from their origin up to the point of export. The supply chain consists of many actors, from input suppliers to farmers, traders, transport and other service providers, and processors.

Figure 2: Supply Chain Analysis

Quality Control Unit for Cacao

After the purchase of the beans, the goods are inspected by the Quality Control Unit of COCOBOD to ensure that the cocoa meets the set standards for cocoa. Ghana Cocoa Board strives to meet the evolving trade quality required by their customers. Ghana remains the top producer regarding the quality bulk cocoa. On the other hand, the CMC remains the most reliable supplier of premium quality cocoa from origin. The minimum quality standards set by Ghana Cocoa Board exceed the respective set in the international cocoa market for the trade in Good Fermented Cocoa. Furthermore, quality control is strict, with 3 stages of quality inspection before it is shipped.

In achieving these set standards, the QCD agent certifies the produce with a tamperproof metal seal attached to the jute bag of weighed cocoa. The jute sack is perforated to allow for air circulation during transportation and maintain the 7% moisture level requirement, as well as absorb excess moisture when the cocoa is being shipped in containers. The sack has the weight, country of origin, and content written on it. Once the bag is sealed, the cocoa remains in the custody of the buyer until it is taken over, and it is a criminal offense to de-seal without the express approval of the Quality Control agent.

Table 3: Quality Specifications: for Ghana Cocoa Beans

| Maximum Defect Levels | |||

| Grade | Mouldy | Salty | Other Defects |

| Grade 1 | 3% | 3% | 3 % |

| Grade 11 | 4% | 8% | 6% |

Source Cocobod

Collection, Haulage & Storage

The graded and sealed cocoa remains in bags until secondary evacuation by the LBCs using either their own trucks or private cocoa haulers to designated take-over points such as Tema port, with a storage capacity of 255,000 tonnes (which is 33% of the total cocoa exports), Takoradi port with 233,000 tonnes (representing 30% of the total cocoa exports) and an inland port at Kaase, Kumasi also receives 67,000 tonnes (thus 9% of the cocoa exports) as at 2020. These takeover points are the final destinations of cocoa products from the LBC’s to COCOBOD.

Haulage

Registered private transport companies haul cocoa from the countryside to designated takeover centres for a fee. They are given education in the handling of cocoa in transit. They are organized under the Cocoa Hauliers Association of Ghana. The major transporters serving this sector are:

- Global Haulage.

- Gelloq Haulage.

- Amtrak Ghana Ltd.

- Vehrad Transport & Haulage Co. Ltd.

- Global Cargo & Commodities Ltd

The price of haulage from each of the 65 cocoa districts to the ports is also regulated by the PPRC. This price is influenced by the mileage and nature of the road network to cover the cost of haulage from farm gates to takeover centers and the port.

Further reading:

Cacao production: Challenges and Management Strategies

Cacao Variety Selection and Propagation

Cacao Soil requirements and Planting distances

Water needs and Irrigation of Cacao

Cacao Fertilization and Nutrient Requirements

Cacao Plant Protection – Major Stresses, Disease and Pest of Cacao

Cacao tree Pruning

Yield, Harvest, Handling and Storage of Cacao

Sales, Trading, and Shipping Cocoa Beans

References

Abara, I. O., and Singh, S. (1993). Ethics and biases in technology adoption: The small-firm argument. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 43(3-4), 289-300.

Adamu, C. O. (2018). Analysis of access to formal credit facilities among rural women farmers in Ogun State, Nigeria. Nigeria Agricultural Journal, 49(1), 109-116.

Adu-Asare, K. (2018). Cocoa farming business, financial literacy and social welfare of farmers in Brong-Ahafo Region of Ghana (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Coast).

Ahenkorah, Y. (1981). Influence of environment on growth and production of the cacao tree: soils and nutrition. In Actes, Douala, Cameroun, 4-12 Nov 1979/7 Conference internationale sur la recherche cacaoyere= Proceedings, Douala, Cameroun, 4-12 Nov 1979/7 International Cocoa Research Conference. Lagos, Nigeria: Secretary General, Cocoa Producers’ Alliance, 1981.

Akudugu, M. A., Guo, E., and Dadzie, S. K. (2012). Adoption of modern agricultural production technologies by farm households in Ghana: what factors influence their decisions?

Ali, E. B., Awuni, J. A., and Danso-Abbeam, G. (2018). Determinants of fertilizer adoption among smallholder cocoa farmers in the Western Region of Ghana. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 4(1), 1538589.

Ameyaw, G. A., Dzahini-Obiatey, H. K., and Domfeh, O. (2014). Perspectives on cocoa swollen shoot virus disease (CSSVD) management in Ghana. Crop Protection, 65, 64-70.

Aneani, F., Anchirinah, V. M., Owusu-Ansah, F., and Asamoah, M. (2012). Adoption of some cocoa production technologies by cocoa farmers in Ghana. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 1(1), 103.

Bonabana-Wabbi, J. (2002). Assessing factors affecting adoption of agricultural technologies: The case of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in Kumi District, Eastern Uganda (Doctoral dissertation, Virginia Tech).

C. Streck, A. Kroeger, S. Koenig, A. Thomson, Forest, and Climate-Smart Cocoa in Cˆote D’Ivoire and Ghana: Aligning Stakeholders to Support Smallholders in Deforestation Free-Cocoa, The World Bank, 2017, pp. 1–57

Danso-Abbeam, G., Addai, K. N., and Ehiakpor, D. (2014). Willingness to pay for farm insurance by smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana. Journal of Social Science for Policy Implications, 2(1), 163-183.

Dormon, E. V., Van Huis, A., Leeuwis, C., Obeng-Ofori, D., and Sakyi-Dawson, O. (2004). Causes of low productivity of cocoa in Ghana: farmers’ perspectives and insights from research and the socio-political establishment. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 52(3-4), 237-259.

Doss, C. R. (2006). Analyzing technology adoption using microstudies: limitations, challenges, and opportunities for improvement. Agricultural economics, 34(3), 207-219.

Giovanopoulou, E., Nastis, S. A., and Papanagiotou, E. (2011). Modeling farmer participation in agri-environmental nitrate pollution reducing schemes. Ecological economics, 70(11), 2175- 2180

Hailu, E., Getaneh, G., Sefera, T., Tadesse, N., Bitew, B., Boydom, A., … and Temesgen, T. (2014). Faba bean gall; a new threat for faba bean (Vicia faba) production in Ethiopia. Adv Crop Sci Tech, 2(144), 2.

International Cocoa Organization (ICCO), (2008). Manual on pesticides use in cocoa. ICCO Press releases of 10 June 2008 by ICCO Executive Director Dr. Jan Vingerhoets. International Cocoa Organization (ICCO), London.

Kehinde, A. D., and Tijani, A. A. (2011). Effects of access to livelihood capitals on adoption of European Union (EU) approved pesticides among cocoa producing households in Osun State, Nigeria. Agricultura Tropica et Subtropica, 54(1), 57-70.

Khanna, M. (2001). Sequential adoption of site‐specific technologies and its implications for nitrogen productivity: A double selectivity model. American journal of agricultural economics, 83(1), 35-51.

Kongor, J. E., Boeckx, P., Vermeir, P., Van de Walle, D., Baert, G., Afoakwa, E. O., and Dewettinck, K. (2019). Assessment of soil fertility and quality for improved cocoa production in six cocoa growing regions in Ghana. Agroforestry Systems, 93(4), 1455-1467.

Kumi, E., and Daymond, A. J. (2015). Farmers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the Cocoa Disease and Pest Control Programme (CODAPEC) in Ghana and its effects on poverty reduction. American Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 7(5), 257-274.

M. Kozicka, F. Tacconi, D. Horna, E. Gotor, Forecasting Cocoa Yields for 2050, 49,

Bioversity International, Rome, Italy, 2018, ISBN 978-92-9255-114-8.

MoFA, 2010. Production of major crops in Ghana, PPMED, Accra, 12 pp.

Namara, R. E., Horowitz, L., Nyamadi, B., and Barry, B. (2011). Irrigation development in Ghana: Past experiences, emerging opportunities, and future directions.

Nandi, R., and Nedumaran, S. (2021). Understanding the aspirations of farming communities in developing countries: a systematic review of the literature. The European Journal of Development Research, 33(4), 809-832.

Ngala, T. J. (2015). Effect of shade trees on cocoa yield in small-holder cocoa (Theobroma cacao) agroforests in Tabla, Centre Cameroon (Doctoral dissertation, Thesis, crop sciences. University of Dschang, Cameroon).

Ofori-Bah, A., and Asafu-Adjaye, J. (2011). Scope economies and technical efficiency of cocoa agroforesty systems in Ghana. Ecological Economics, 70(8), 1508-1518.

Ogunsumi, L. O., and Awolowo, O. (2010). Synthesis of extension models and analysis for sustainable agricultural technologies: lessons for extension workers in southwest, Nigeria. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America, 1(6), 1187-1192.

Okojie, L. O., Olowoyo, S. O., Sanusi, R. A., and Popoola, A. R. (2015). Cocoa farming households’ vulnerability to climate variability in Ekiti State, Nigeria. International Journal of Applied Agriculture and Apiculture Research, 11(1-2), 37-50.

Okyere, E., and Mensah, A. C. (2016). Cocoa production in Ghana: trends and volatility. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 5 (3), 462-471.

Opoku-Ameyaw, K., Oppong, F. K., Amoah, F. M., Osei-Akoto, S., and Swatson, E. (2011). Growth and early yield of cashew intercropped with food crops in northern Ghana. Journal of Tropical Agriculture, 49, 53-57.

Oyekale, A. S. (2012). Impact of climate change on cocoa agriculture and technical efficiency of cocoa farmers in South-West Nigeria. Journal of human ecology, 40(2), 143-148.

Wessel, M., and Quist-Wessel, P. F. (2015). Cocoa production in West Africa, a review and analysis of recent developments. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 74(1), 1-7.

World Bank (2011). Supply Chain Risk Assessment: Cocoa in Ghana. Ghana Cocoa SCRA Report.

World Bank. 2007. World development report 2007: Development and the next generation. Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Wossen, T., Berger, T., Mequaninte, T., and Alamirew, B. (2013). Social network effects on the adoption of sustainable natural resource management practices in Ethiopia. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 20(6), 477-483.

( Dohmen, et al. 2018) Temperature changes, drought, and prolonged dry season affect the flavor and overall quality of the product

(Neilson, 2007) Unlike Farmers in West Africa, Cocoa farmers in Latin America tend to ferment the cocoa pulp surrounding the beans using wooden boxes. In Indonesia, farmers rarely take part in the fermentation process because their production is valued mostly for cocoa butter which is unaffected by fermentation