Weed Management in Wheat Farming

This post is also available in:

This post is also available in:

![]() Español (Spanish)

Español (Spanish) ![]() Français (French)

Français (French) ![]() Deutsch (German)

Deutsch (German) ![]() Nederlands (Dutch)

Nederlands (Dutch) ![]() हिन्दी (Hindi)

हिन्दी (Hindi) ![]() العربية (Arabic)

العربية (Arabic) ![]() Türkçe (Turkish)

Türkçe (Turkish) ![]() 简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified))

简体中文 (Chinese (Simplified)) ![]() Ελληνικά (Greek)

Ελληνικά (Greek) ![]() Português (Portuguese (Brazil))

Português (Portuguese (Brazil)) ![]() polski (Polish)

polski (Polish)

The wheat crop can be infested with a great variety of weed species. This is because it grows under diverse agroclimatic conditions, different irrigation methods, different tillage systems, and crop rotation sequences.

The reduction in the height of modern wheat varieties and the loss of specific competitive characteristics have led to an increase in weed problems in many areas. Except for the direct competition with the crop plants for resources, like space, sun, water, and nutrients, weeds can “harm” the crop by serving as host for important pests and diseases (e.g., oidium) as well as contaminating the purity of harvested wheat grains and thus decreasing the quality. Depending on the region, the weed species that prevail and their population size, the soil characteristics, the sowing time, and the crop density, the yield losses caused by weeds usually range between 10 and 80%, with an average closer to 20-30% (Chhokar et al., 2012). In some areas-countries, the crop losses due to weeds are equivalent to 20% of the gross value of the wheat crop (1).

While the chemical control methods offered a cost-effective solution for many decades after the “Green Revolution,” the excessive use of herbicides and the lack of rotation of the different active compounds available gave rise to the development of herbicide-resistant weed species in many areas worldwide. To efficiently control the most important weed species, the farmer has to know some principles and follow a holistic approach by applying integrated management techniques.

Know your “enemy.”

Regardless of the measures used, the effectiveness of weed control depends on recognizing the weed populations that exist in the field, their location, and of course, the early observation and management actions. The farmer needs to keep data concerning weed species presence yearly, so he/she knows what preventing or control measures to apply and which of these gave the best results. The older weed records will facilitate the selection of an appropriate pre-emergence herbicide and the in-time application of post-emergence products when the weeds are still in an early stage, and the chemical control is more effective.

For winter wheat, usually planted in early-mid autumn, the 2 more challenging periods for weed competition are during emergence and later on at the start of spring when the rest of the weeds (summer weeds) germinate, and winter wheat becomes multitudinous. For spring wheat, most problems arise during the first stages of the crop when the wheat plants are not so competitive compared to weeds. Any changes that the farmer will make in the agricultural practices he/she uses, for example, a transition from conventional tillage to a no-tillage system or from dry cultivation to irrigation, are expected to cause a shift in the weed population. Knowing the weed species and their physiology will help the farmer anticipate this early enough and take any necessary measures.

Most of the weeds common in wheat fields that put at risk the crop yield belong to the Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, Geraniaceae, Poaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Rubiaceae families. At the species level, the most important weeds are listed in the following table.

| Scientific Name | Common Name |

| Avena sativa, A. ludoviciana, Α. sterilis | Wild oat |

| Phalaris brachystachys Link. & P. minor Retz. | Canarygrass |

| Alopecurus myosuroides Huds. | Blackgrass |

| Lolium multiflorum L. and L. rigidum | Ryegrass |

| Poa annua L. | Bluegrass |

| Sinapis arvensis L. | Wild mustart |

| Galium tricornutum L. | Catchweed bedstraw |

| Ranunculus arvensis L. | Corn buttercup |

| Geranium dissectum L. | Cut-leaved crane’s bill |

| Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. | Canada thristle |

| Rumex dentatus L | Toothed dock |

| Medicago denticulata | California burclover |

| Amaranthus tuberculatus | Waterhemp |

| Kochia scoparia | Kochia |

Other common weed species are: Papaver rhoeas L., Veronica persica Poir., Arthemis arvensis L., Alopecurus myosyroides, Bromus spp., Matricaria spp., Polygonum aviculare, Gallium aparine, Cirsium arvense, Malva parviflora, Capsela bursa-pastoris, Fumaria officinalis Chenopodium spp., Angallis spp. and Stellaria media (2, 3; Pala, & Mennan, 2017, 2021).

Prevention and weed management strategies

The farmer needs to rotate and combine the weed management measures to control the different weed species effectively and sustainably for a long period of time. It is best to calculate the economic threshold and know the critical weed density (per species) to decide on the need, time, and type of weed control application. Especially the critical weed density could differ a lot among weed species depending on the yield losses they can cause. For example, when 4 plants of grass wild oats per square meter or 1 plant of broad-leaved wild mustard per square meter are recorded on the field, control should be started (Kadioglu et al., 1998; Mennan, 2003). The goal of all weed management measures is to decrease the population of weeds in the field when the crop is present and reduce the soil’s weed seed bank. For this reason, the control is more effective when performed early and, of course, before weeds start producing seeds. You should always consult your local licensed agronomist.

- Mechanical weed control practices:

Before seeding the wheat, we can perform primary tillage to give it a clean start. It is essential to clean and disinfect any machinery used that can transfer new weed seeds into our field. Despite its effectiveness at the beginning of the cultivation season, manual or mechanical weeding is not widely used, especially in larger fields. The main reason for this is the very high cost of the method, which can be even 8 times more expensive than chemical control and up to 80 times more time-consuming. Additionally, many weeds (e.g., P. minor and Avena ludoviciana) resemble wheat plants in the early growth stages, making it very difficult to distinguish and remove them within the rows.

Limited/no-tillage has become a very popular and largely applied technique used in wheat crops. While it is considered a cost-effective and sustainable weed management system, repeated implementation over the years may change the balance among the weed species, favoring weeds like Rumex dentatus and Malva parviflora. Finally, since the weed control measures do not stop after wheat harvest, it is essential to take action to increase their effectiveness. Crop residues (straws) of around 7.5 tonnes per hectare that remain on the field can reduce the weed infestation by 40%. The farmer should avoid burning the residues. This practice has catastrophic environmental impacts, while the ash drastically reduces the effect of some herbicides used during that period (pendimethalin and isoproturon) (3).

- Crop management (density, sowing period, fertilization):

Any actions that increase the competitive ability of wheat against weeds can be beneficial. Based on experimental results, an increase in plant density with closer row spacing (15 cm – 5.9 in) has significant positive results in weed population reduction (Mongia et al., 2005). For example, reducing row spacing from 50cm to 25cm (19.7-9.8 in) in durum and common wheat crop decreased the fleabane population by up to 44% (4). In all cases, use only certified and free from weed seeds reproduction material to start your crop.

Early sowing can also give a head start in the crop, especially against P. minor. However, the sowing date should not deviate too much from the suggested time because it will result in yield loss. Finally, measures that protect or increase crop vigor like fertilization and plant protection should be applied when needed. During or before wheat seeding, the farmer should apply fertilizers 2-3 cm (0.8-1.2 in) below the seed and avoid broadcasting it. Generally, the phosphatic fertilizers promote the growth of broadleaved weeds, whereas nitrogen boost the grass weeds (Chhokar et al., 2012).

- Crop rotation:

The principle is to rotate wheat with crops that are stronger competitors against the most critical weeds for wheat. Additionally, cultivating different crops in the same field with diverse seeding and maturity moments makes it easier to break the life cycle of certain dangerous annual weeds. Crops like barley, turnip rape, sugar beet, sugarcane, sunflower, berseem, corn, dry bean, and canola can be used in the crop rotation sequence with good results (Jalli et al., 2021, 5, 6). This strategy has been proven very effective in controlling Phalaris minor. However, when wheat succeeds rice, which is the typical scheme in India, the weeds are favored and germinate earlier in the season (autumn) due to the sufficient soil moisture (3).

To protect the next crop, the farmer should avoid using very persistent, residual herbicides that can stay active in the soil for several months. The problems will be extensive, especially if the following crop belongs in the plant target category of the herbicide used (e.g., broadleaves).

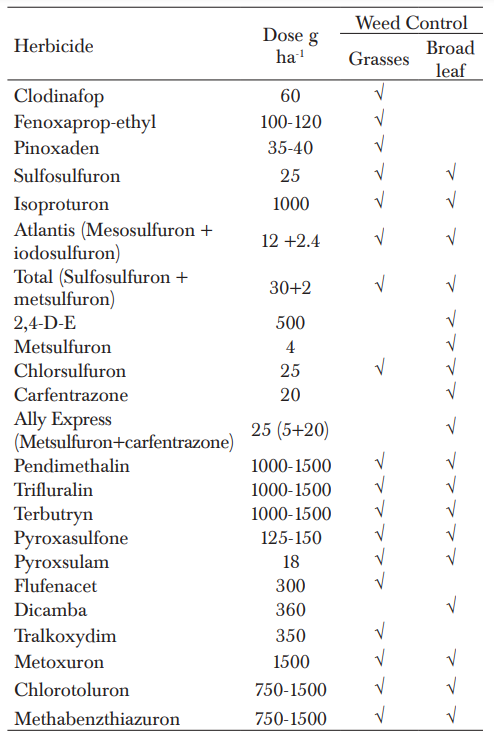

- Chemical control – Herbicides:

Chemical herbicides are still the most popular weed control measure in wheat. However, it is essential to pay attention to the type of the active compound, the dose, the method used, and the time of the application. Remember always to rotate herbicides (site of action) and use products that include multiple sites of action (in tank-mixed, pre-packaged or sequential). All these are essential measures to avoid or limit the problems caused by the development of herbicide resistance in weeds. Each year new weed species become resistant to more active compounds. To avoid any surprises in the field, check the constantly renewed lists of herbicide-resistant weeds. You should always consult your local licensed agronomist before deciding on herbicide use.

The chemical control of weeds can be performed with pre-emergence herbicides that have some residual action and can control the first few flushes of germinating weeds in the early growth stages of the crop. Such herbicides can include imazapyr, chlorsulfuron, atrazine, metsulfuron-methyl, and simazine. Be very careful or avoid using chlorsulfuron-based herbicides since it remains active in the soil for many months and can damage legumes and oilseeds that may follow wheat in the field (6). You should always consult your local licensed agronomist before deciding on herbicide use.

After the emergence of the crop, we can implement chemical weed control from the 3-leaf period of the wheat to the end of tillering (Pala and Mennan, 2021). Always check the product’s label to see the maximum wheat growth stages and the ideal weed growth stages for application. Most herbicides should not be applied after Feeke’s Stage 6 (the first node of the stem is visible) because there is a high risk for herbicide injury. There are very few herbicides that can be applied until Feeke’s Stage 8 (last leaf just visible) and contain as active compounds the Bromoxynil Octanoate and Bicyclopyrone (7). You should always consult your local licensed agronomist before deciding on herbicide use.

(Chhokar et al., 2012)

List of wheat herbicides, their optimum doses, and target group

Keep in mind that low temperatures can reduce the efficiency of the herbicides. As a general rule, do not apply any herbicides when the temperature is less than 10 °C (50 °F) (7). You should always consult your local licensed agronomist before deciding on herbicide use.

Attention:

- You should always consult your local licensed agronomist before deciding on herbicide use.

- Use herbicides only when necessary and best with more space-precise applications (patch management).

- Avoid two applications in a row with herbicides having the same mode of action.

- Don’t reach for glyphosate for knockdown of weeds.

References

- https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grownotes/crop-agronomy/northernwheatgrownotes/GrowNote-Wheat-North-06-Weeds.pdf

- http://www.opengov.gr/ypaat/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2013/07/sitari.pdf

- https://sawbar.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Weed-managment-stratergies-in-wheat-A-review.pdf

- https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grownotes/crop-agronomy/northernwheatgrownotes/GrowNote-Wheat-North-06-Weeds.pdf

- https://extension.umn.edu/small-grains-crop-and-variety-selection/small-grain-crop-rotations

- http://www.daff.qld.gov.au/plants/field-crops-and-pastures/broadacre-field-crops/wheat/plantinginformation

- https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/herbicide_options_for_weed_control_in_winter_wheat_things_to_consider

Chhokar, R. S., Sharma, R. K., & Sharma, I. (2012). Weed management strategies in wheat-A review. Journal of Wheat Research, 4(2), 1-21.

Jalli, M. J., Huusela, E., Jalli, H., Kauppi, K., Niemi, M., Himanen, S., & Jauhiainen, L. J. (2021). Effects of crop rotation on spring wheat yield and pest incidence in different tillage systems: a multi-year experiment in Finnish growing conditions. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 214.

Kadioglu, İ., Uremis, I., Ulug, E., Boz, O., Uygur, F.N. 1998. Researches on the economic thresholds of wild oat (Avena sterilis L.) in wheat fields in Çukurova region of Turkey. Türkiye Herboloji Dergisi, 1 Mennan, H. 2003. Economic thresholds of Sinapis arvensis (wild mustard) in winter wheat fields. Pakistan Journal of Agronomy, 2(1): 34-39.(2): 18-24.

Mongia AD, Sharma RK, Kharub AS, Tripathi SC, Chhokar RS, and Jag Shoran (2005). Coordinated research on wheat production technology in India. Karnal, India: Research Bulletin No. 20, Directorate of Wheat Research. 40 p.

Pala, F., Mennan, H. 2017. Determination of weed species in wheat fields of Diyarbakir province. Bitki Koruma Bülteni, 57(4): 447-461

Pala, Fırat & Mennan, Hüsrev. (2021). Common Weeds in Wheat Fields.

Wheat Plant Information, History and Nutritional Value

Principles for selecting the best Wheat Variety

Wheat Soil preparation, Soil requirements, and Seeding requirements

Wheat Irrigation Requirements and Methods

Yield-Harvest-Storage of Wheat

Weed Management in Wheat Farming